This article is a co-production between RedSnap and Fincog

This is the age of the digital platform economy. And it’s putting banks at risk.

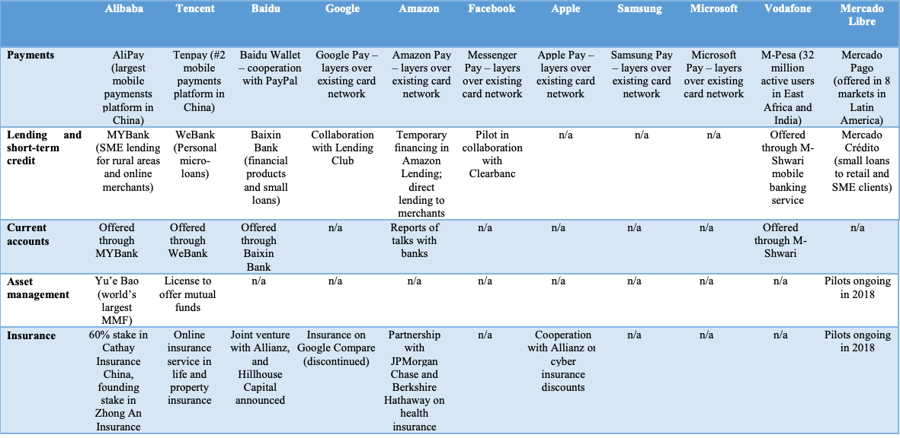

Online ecosystems like Amazon, Google, Facebook, eBay, Alibaba, and GO-JEK bring people together to contribute, interact, buy, sell and more. They’ve already irreversibly changed the retail landscape. Now, by introducing financial products like payments and consumer credit, they want to eat the banks’ lunch.

What can banks do to fight back? This is more than just straightforward competition for banks.

Why? Because the terms of engagement are different. For a start, as online intermediaries, bringing vendors and customers together, platforms are primarily digital entities, a set of algorithms that serve to organise and structure economic and social activities. They simply provide the ecosystem to support sales of products and services whose costs and associated risks land elsewhere.

Banks, except for the newest fintech contenders, have a physical estate whose costs need to be covered. Banks create their own products and services and bear the risk of success or failure. As a result bank financial products almost always need to be profitable.

For the mega platforms like Amazon, financial products only need to generate more footfall and more overall use of the platform. Cross-subsidisation allows for lower margins and spreads costs.

For banks, this is a clear problem.

A new paradigm

Let’s consider the evidence. These global platforms already have far larger customer bases than banks. Compare Facebook’s 2 billion active users to ING Group’s 37 million customers. Their potential markets are larger too.

They don’t have to wrestle with the sort of legacy systems large banks have either. That makes it easier to do everything from customer analytics to launching new services.

Regulation helps them too. In Europe, PSD2 means that as registered third-party providers, they can gain access to bank customer data (providing they adhere to GDPR and bear increasing customer sensitivities about data privacy in mind).

Let’s look at GO-JEK for a non-European example. GO-JEK in Indonesia is a complete lifestyle platform, offering transportation, food delivery, logistics and more. Initially, payment for platform services was cash only. That was limiting and now they offer GO-PAY, now Indonesia’s fourth biggest wallet service. This allows users to pay for services and bills, make P2P transfers, links to bank accounts and enables phone credit top-ups. Users can meet most of their financial needs through GO-PAY. Their bank account only serves as a means to bring money into GO-PAY and as a result, the banks lose transaction and service-related revenue. In 2017 GO-PAY accounted for 30% of e-money transactions. More recent estimates suggest it sees 1.5 million daily transactions.

Source: FSB

That’s just one example where banks are losing traction. A recent report from the Financial Stability Board (FSB) on “Fintech and market structure in financial services: Market developments and potential financial stability implications,” suggests that the activities of these platforms could even impact bank stability.

What can banks do to fight back?

Strategic options for banks

We’ve identified three potential strategies that banks could follow.

1. Partner with platforms

Many banks have been open and welcoming towards the idea of collaborating with fintechs, recognising that it’s a good way to benefit from innovation. Perhaps they could extend that openness towards the platforms?

The benefits could extend to:

• Improved access to data

• A fast track to new technical solutions

• Enhanced customer experience.

Banks could act as a distribution channel for the platforms, allowing them to provide the bank customers with improved customer services. This would require agreement about which aspects of the customer facing service the banks retain responsibility for and which the platforms take on. It has the potential benefit of boosting bank firepower in competition against other banks.

There is also the potential here for leveraging remaining physical bank branches for distribution purposes for the platforms.

If banks don’t follow this path, they risk losing customers to competitors with better products and better customer experience.

Apple Pay and Google Pay provide good existing examples of bank collaborations.

2. Compete with platforms

To compete effectively, banks will need to shake up and improve their customer offer, becoming more competitive, more efficient and more cost effective.

However banks already have some undeniable advantages over the platforms - for many, there is the physical branch network and the ability to offer multi-channel service. For some types of customer, legacy bank brands offer far greater customer trust than new technology players can, especially in the light of recent data sharing scandals.

Banks also have the ability to create their own platform approach, either independently or working with fintechs. This brings them the benefits of the platform approach - easy innovation, speed to market and greater agility - while retaining full control of the customer relationship.

To do this, though, they must review and redefine their strategy to ensure they stay relevant.

Royal Bank of Canada offers a great example of this approach with the digital alternative investment platform it launched together with its fintech partner, Artivest. The collaboration helped RBC take the platform to market in as little as 18 months.

3. Ignore the platforms

Finally, banks could simply choose to ignore the platforms. Perhaps they don’t believe that the platforms are competition. Perhaps they believe it’s too hard to change their technology to compete. Perhaps they believe their personal touch is differentiation enough.

If they take this position they can only focus on boosting existing strengths and relationships and providing a level of service that tech platforms simply can’t because of their lack of branch infrastructure.

We’ve mentioned the trust premium many banks already enjoy. For example, many older customers like the traditional way of banking and don’t want things to change. They won’t consider turning to a tech platform for financial services and they value a personal banking relationship with a traditional institution.

That’s what spurred the creation of Metro Bank in the UK in 2010, the first UK high street bank to launch in over 150 years. This personal approach can be hard to put a price on and it’s also one that continues to thrive at the wealthier end of the retail banking market too.

Conclusion

Whichever route banks choose to take, they can’t stand still and they can’t ignore the fact that for a growing number of customers, financial services from the likes of Alibaba or Amazon are very attractive indeed. At a minimum, banks should rethink business models and customer strategies and consider the benefits of collaboration and platform models in one shape or another.

Because, if there’s one thing that is absolutely clear, the global platforms aren’t going away.